ESSAYS

THE DREAMING UNIVERSE OF JEAN KAZANDJIAN

BY GLORIA F. ORENSTEIN

PROF. COMP. LIT. AND

GENDER STUDIES

UNIV. OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

LOS ANGELES, CA.

As we enter the visual world of Jean Kazandjian we encounter a cosmos in which everything is alive and everything is capable of dreaming. Not just Man, as Surrealist Andre Breton had defined him: “Man, that inveterate dreamer”i , but, Woman, the landscape, and even art. Everything that is created has a spirit, and it is the spirit of a Dreaming Being. Kazandjian has captured them all in their moments of reverie, as their spirits wander non-locally throughout the universe, and plunge into memories of the past, visions of the future, or into parallel lives in other dimensions...

The mythos that Kazandjian’s work evokes is that of The Great Mother, The Earth Mother (Anahid in Armenian mythology). This Venus, Madonna, Goddess, Woman is not the domesticated patriarchal image of woman linked to earth in a traditional way, not the passive object of the male gaze, but a uniquely new/and also ancient, non-androcentric Subject. The artist’s gaze perceives the female as both the matrix of all life and the empowered presence, who makes reality cohere, and whose consciousness presides over all of creation. I would venture to say that for Kazandjian, the female is the generic human. She enfolds and gives birth to all living things, and his definition of living things includes art. This Mother Goddess also represents both painting and fecundity, for as Jean Kazandjian has mentioned to me: “painting gives birth to extraordinary children.”ii

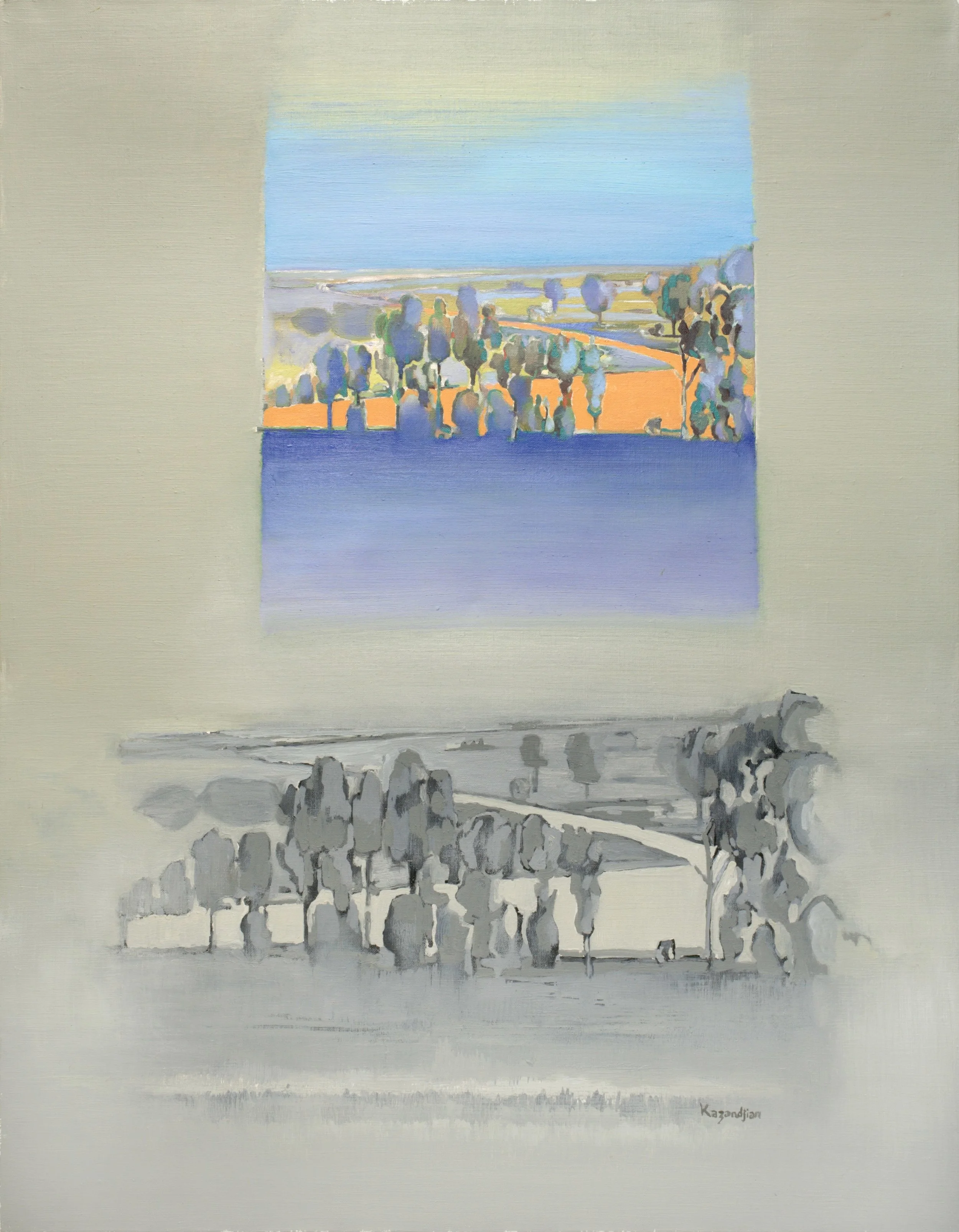

The meaning of these words becomes clear in works such as “3 Séquences d’un Paysage” (1993), “Paysage et Son Concept” (1995) and “Concept d’un Paysage” (1995). In these paintings we glimpse the animate world of trees and of the fertile landscapes in their intimate, meditative moments, in their day-dreams of themselves as light-infused, as living elsewhere, as having been birthed into other realms, and once finding themselves there, undergoing subtle transformations. Changes in color convey the energies and auras of these other worlds—the blue world, the golden world, the off-white world. These worlds are the dream worlds and the resurrected worlds inspired by the reveries of the painted world that first represented the real world, and then took wing.

There are also painted worlds that do not represent the real world. They are, themselves, portraits of art works. But all great art has spirit, and paintings also dream of themselves as transformed in their most meditative moments of self-contemplation. We notice with astonishment how his “Séquences - Vénus de Giorgione” (1995) and “L’Annonciation – Autre Concept d’Après Léonard De Vinci” (1993) seem to incarnate the Surrealist metaphysics which has always claimed that the imaginary tends to become real. If we let our gaze travel from bottom to top in the painting of “Séquences - La Vénus de Giorgione” we note that the image becomes more focused, contains more details, and ultimately attains a higher degree of realistic clarity at the top of the work. One might speculate that the artist’s dream of the Venus, as she ascends the ladder of dream, begins to merge with a Venus that would be perceived with waking vision. Here is the aesthetic expression of the “communicating vessels”, as Breton had envisaged them, where waking and dreaming merge their contents so completely that another reality, a Surreality comes into existence. Surreality in Jean Kazandjian’s oeuvre is not eccentric. Just as the female is the generic, in this universe, Surreality is the norm, for the cosmos is alive, and is both dreaming and being dreamt. Reading the painting this time from top to bottom, we might imagine Giorgione’s model dreaming her way into his art, and then the painting slipping away from one level of painted life, to its incarnation as a dream, and then to yet another level of embodiment in some other realm of desire... This is an artistic vision in which everything, both painted and real is interconnected. Every creation is a potential dreamer as well as a potential beloved object of someone (or something’s) dreaming gaze. Through the many levels of trance, inspiration, meditation, and reverie, we come to know the secret life of Venus, the colorful desires of the trees, the spiritual intention of the Angel of the Annunciation, and the astounding receptivity of the Madonna. All of these beings have psychic lives and engage in active imaging. In “L’Annonciation – Autre Concept d’Après Léonard De Vinci”, scanning the painting from bottom to top, we glimpse the enigmatic suggestion of a divine level of reality, one that is not perceived through retinal vision, yet one that portends a magnificent future event that will then transpire in blaze of color, but in a smaller version (portrayed at the top of the painting), for it will be situated in historic time and space rather than in an ideal/archetypal or sacred realm of potential miracle.

In “Séquences - Paysage et Nu Allongé” (1993), the Venus figure is asleep at the foot of the painting. As we look upwards we notice how the living world, and all of nature (in its dream state and also in its realism) are both extraordinary dreams of The Great Earth Mother. Each level is the representation of a different realm of the real, but this is the expanded real, the Surreal, where dream and art cohabit a luminous universe suggested by the golden light surrounding the Venus. Before the Biblical Fall, all creatures, great and small, human, non-human and divine lived harmoniously in the Garden of Eden. In the art of Jean Kazandjian, before our Fall into the Mickey Mouse Disneyworld of freeways and malls, all creatures communed in the Garden of Earthly Delights, of Surreality, and of expanded consciousness. Art, dream, reality and the offspring of their imaginations co-habited and intermingled in a pre-patriarchal dreaming garden, embodied in the mythic vision of Jean Kazandjian.

The artist’s quest to discover the hidden dimensions of reality began when as a child making art, he would tear through the paper he was drawing on in order to see what lay beyond the surface in the hidden interior. Over time he explored dimensionality and perspective by studying architecture. Even his dream world is inhabited by structures that are also on the move as in “Séquences - Paysage Vertical (1997). In this work the woman’ presence is the foundation of the silver, gold, persimmon dream worlds speeding by in film strips. Here the architectural segment of a staircase is fleeing with the other dream-beings and objects that are migrating and traveling vertically. It is the female who grounds a world that seems to be in upheaval, and might otherwise escape from us entirely. Having migrated from Lebanon to Paris and then to Los Angeles, Jean Kazandjian, of Armenian heritage, has passed through the many stages depicted in “Séquences - Les Migrants” (1996). Families, both contemporary and historic migrate through his vistas as in “ Séquences d’un Ichabane - Les Migrants ” (1997) who transport their belongings on pack mules, traveling west, always ascending, moving from darkness to light. As each filmstrip reveals a segment of the journey, we witness their passage as if the camera were set in slow-motion to depict the dream of an ancient epic migration. The camera speeds up when contemporary migrants pass through the city in “Séquences - Les Migrants” (1996). They seem to fade and morph cinematically through space and time as they emerge, spirit-like, almost out of place against the background of trucks and cars and busy passengers. These ancestral migrants may even be escaping our modern, overcrowded cities. They may be seeking life closer to nature and further from the traffic that blocks their passage. Staircases appear in sequences in: “Séquences – Nu descendant l’Escalier” (2000 diptych). They may be dreaming of becoming leaves, as they also morph through a sequence of still shots into autumn leaves in gold, rose and reds.

Women are often linked to the landscape and to the staircase. Women ascend and descend the staircases, for they are always in motion, moving forward and mostly upwards, towards the light. Even if they appear to be descending as in “Defile III” (2002), they are rushing to the light. Another unique perspective is revealed as the viewer’s gaze comes from above, from the region of light. Are we looking down from a balcony, from an airplane with a zoom lens? Or are we flying by on our own shamanic journeys? Glancing down from on high, we see that the woman is in motion, but she is also multiple and identical. Is she cloned? Is she living in parallel universes? Are there many women or is there just one seen through many lenses and mirrors? Images flow past us all too quickly. They change color as in “Séquences—Trois Jardins et Personnages de Profil” (1999), so that we only perceive fragments of the frame of the face or the film strip of the garden. In “Femme et Escalier en Trois Mouvements” (1999). the feeling is one of trying to slow down the film in order to focus on the beauty of the woman, whose head changes ever so slightly, as her image rushes by. We want to see everything in slow motion - the woman, the stairway, so that we may take time to contemplate the mystery of the steps leading upwards and towards the light. We move from obscurity to color and then to light, but time is fleeing like the Migrants, the stairways, the women, the landscapes, and its passage leaves us yearning to penetrate the mystery of the illusion, which can only be partially captured by the filmstrip as recorded by the painted image. The illusion may be our dream or that of those many beings, both human and non-human, who inhabit the various planes of reality and Surreality through which we pass as we migrate through creation seeking a return to life renewed in the Garden, embraced by the light.

Jean Kazandjian’s most recent migration has led him to the gardens and light of Southern California. Once there, he encountered a fallen world of false Edens and pseudo paradises, not an expanded vision of Surreality, but a world of reductive simulacra and commodifed pleasure domes. While a critique of the superficial aspects of contemporary culture is often apparent in his works, Kazandjian’s larger vision for the evolution of our civilization is oriented towards a more positive future. His most fervent dream is that the artistic tradition coming from our European roots can be reconciled with the technologically advanced expressions of beauty in the modern world. His “Venus at Disneyland” (2006) depicts Venus encircled by the ‘Mickeys’ dancing around her.

Here the two worlds collide, yet that collision has resulted in their interpenetration. The Mickeys seem to be traveling through the body of Venus, and one can see that the energy of their dance has the effect of awakening and pleasing her. It is Kazandjian’s hope that the artist of the future, perhaps symbolized by the hand at the center, behind Venus, from which an angel (not a Mickey) issues forth, will incorporate the many positive values of both cultures and produce an integrated vision of a beauty yet to be born.

In 1995, his “Temptations” referenced the painting of the 15th century Flemish artist Hugo Van der Goes, “The Temptation” with Adam and Eve in the Garden. Here a new temptation has replaced that of the apple. It is the dollar bill looming like a billboard in the background. If Woman, as a possible New Eve, is Kazandjian’s image of both salvation and beauty, the artist has painted her in pure white, representing innocence. We find her suggested abstractly, also in white, in many of his seated nudes from this period. This New Eve who will reject the temptations of the future, is delineated more figuratively in “X Possibles” (2002). Here a central nude woman in white is visible through layers of white veils that are painted on the screen. She can be found beyond the veil with the large red X painted on it. The symbolism can be read in many ways. If the enigmatic woman in the white of innocence can only be glimpsed through the veil with the red X, her potential existence lies beyond the veil of the known. She is still partially hidden by the painted veils. Nevertheless her presence shines through from behind the veils at the appointed place (X marks the spot), for her emergence in our world is imminent.

The painted veil prefigures the innovative use of the screen, in Jean Kazandjian’s most recent work. Since the early nineties, the artist has been attaching an almost imperceptible screen about an inch and a half away from the painted canvas. If we look closely we notice that the screen carries its own painted image, and as we move our gaze across the dual- imaged surface, we are slowly able to perceive the one image through/with/ and in the other. From this sudden, subtle depth perception, a third and fourth dimensions appear to emerge, creating a marvelous illusion, and the possibility of seeing in new ways. Already in “Vénus de Milo et Ecran” (1991) the New Eve is linked with Venus, the classical image of beauty. Over a photo portrait in profile of a contemporary woman, Kazandjian has installed a screen with Venus’ torso painted in red upon it. A subtle kinetic movement occurs as the viewer scans the image, and perceives the bright red of Venus, remembered against the photo portrait of the modern woman. The top of the image is washed in a golden ray of light, blending the minds of the two women. This blended double vision of Venus and The New Eve is composed of both past and present. Kazandjian’s contemporary Eve has not forgotten her ancient incarnation as Venus. But she is now turning towards another horizon as she incorporates the memory of her past into what will become her concept of the future In fact, she is looking towards the East, squinting in the light, perhaps trying to catch a glimpse of a New Eden.

In works from 2006, familiar motifs such as that of women ascending, suddenly come to life in three dimensions, as the screen painted red permits us to perceive the nude women climbing the stairs. Somehow the painted screen permits other dimensions to pierce through our previously veiled vision. A work such as “Landscape and Profile” from 2006 presents this revelation to us, as we see through the large brush strokes on the screen to a clearer, deeper vision in reality. The viewer is looking out at nature, the garden or even a junglescape from the porch of a house. The contrast between the architectural order of the balcony and the wild overgrowth of the junglescape just beyond it creates a dualism that is overcome by the artistic power of the screen. Rectangles of color painted on the almost invisible screen permit us to see through the colored brush strokes and painted geometries to yet another view of nature, seen through the veil, with all the metaphoric implications of that expression. Nature is revealed to us as if through a telescope of the interior eye. We become like visionaries of nature in a state of rebirth through a transformation of vision that we accede to only through art.

With the emergence of the screen in Kazandjian’s work, familiar motifs from the past also take on dimensions of monumentality, as they are perceived more accurately through the screen’s ability to permit us to zoom in or take a panoramic view of reality. The painted screen functions like the viewfinder of a camera, bringing us closer to those aspects of our world that will become known to us as we adjust our focus, but are not known to us at present. In a work of 2006 a young man, in bas relief, is becoming conscious of himself in the environment, represented by the fecundity of Mother Earth. He may be the artist of the future, and his mind is immersed in the great alchemical adventure of following one’s inspiration on a quest for the discovery of perfection. That perfection, the gold of the alchemists, the green of the environmentalists, is depicted by the blue of inaccessibility by Kazandjian. Here all polarities, dualisms and opposites (male / female, innocence / knowledge, human / non-human nature, youth / maturity) are reconciled by the perceptual transformations that the screen brings about in our field of vision. When we view the painting in a perfectly lighted space, these alchemical transformations, these reconciliations of complementarities and parallelisms, seem to tear away the veils from our eyes, and reveal the wonders that await us in all the clarity and potency of their imminent manifestation in our world. Paradoxically, the screens unveil what has been hidden. They reveal rather than conceal. In English we speak of “screening” a film before it opens, before it is revealed to the public. Similarly, Kazandjian permits us to “screen” a possible future. This is the artistic and visionary heritage of the future generation, who comes to consciousness with a knowledge that the pure, innocent vision can become a reality once more.

Without evading the realities of the violence, destruction and pollution in our modern cities, Kazandjian still dreams of the triumph of hope and love. In “Kissing Roses” (2001), with the memory of the attack on the Twin Towers in the background, the spirits of two lovers float before us, over the skyscrapers of New York, enfolded in the flowers that have bloomed in their intimate poetic universe. Jean Kazandjian enables us to perceive these magical visions of hope that might otherwise seem impossible to sustain. It is through a belief in the existence of Surreality, a realm where desire and dream are the alchemical forces of transmutation, that we are able to foresee a future rebirth. This is a vision of the Marvelous and of the power of Beauty alive in the world. As Andre Breton has expressed it: “Let us not mince words: the marvelous is always beautiful, anything marvelous is beautiful, in fact only the marvelous is beautiful.”iii Jean Kazandjian’s artistic world is an eloge to the Marvelous and the Beautiful as potent forces for change in which we place our belief in the survival of the human spirit and the regeneration of the natural world.

i Breton, Andre. MANIFESTOES OF SURREALISM (Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1972) p.3.

ii Kazandjian, Jean Personal interview with Gloria Orenstein, Nov. 2006.

iii Op.cit. Breton, Andre. MANIFESTOES OF SURREALISM, P. 14.